Mercury

Preamble

With ESA’s ‘BepiColombo currently en route for Mercury, there is a regain in interest for the innermost terrestrial planet. The crust of Mercury has been the stage for various geological processes, including volcanism, the formation of giant impact basins, but also global contraction and tectonic activity. Each of these processes has profoundly affected the structure, composition, and porosity of the crust. My work on Mercury consists of characterizing the structure of the crust and unravelling geodynamical evolution of the planet using geophysical models.

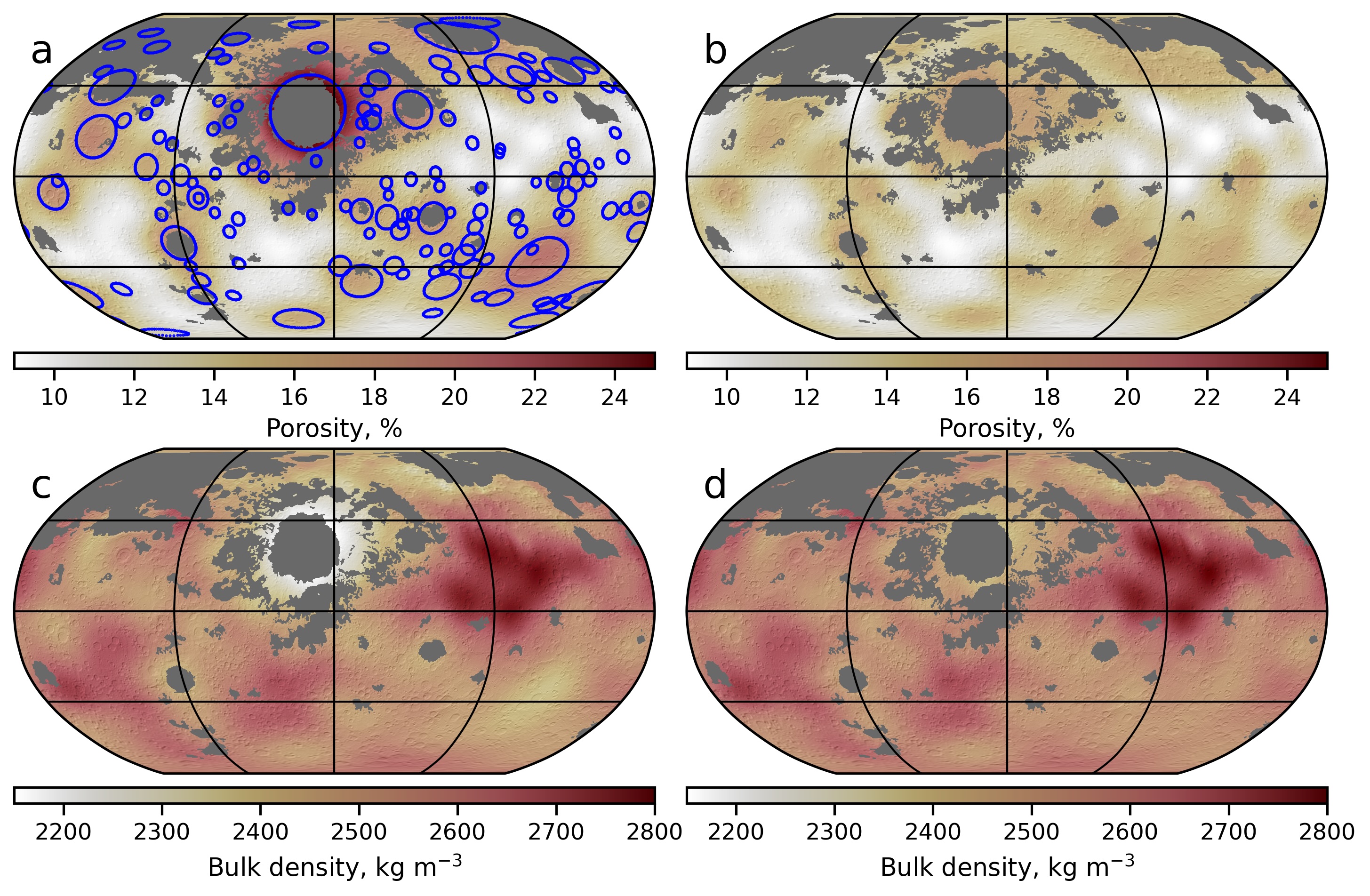

Mercury’s crustal porosity as constrained by the planet’s bombardment history

Knowing the structure of the crust is critical to understanding a planet’s geologic evolution. Crustal thickness inversions rely on bulk density estimates, which are primarily affected by porosity. Due to the absence of high-resolution gravity data, Mercury’s crustal porosity has remained unknown. In Broquet et al. (2024), we use a model that was calibrated to the Moon to relate Mercury’s impact crater population and long-wavelength crustal porosity in the cratered terrains. Therein, porosity is created by large impacts and then decreased as the surface ages due to pore compaction by smaller impacts and overburden pressure. Our models fit independent gravity-derived porosity estimates in the northern regions, where data is well resolved. Porosity in the cratered terrains is found to be 9% to 18% with an average and standard deviation of 13±2%, indicating lunar-like crustal bulk densities of 2565±70 kg m-3 (Figure 1) from which updated crustal thickness maps are constructed.

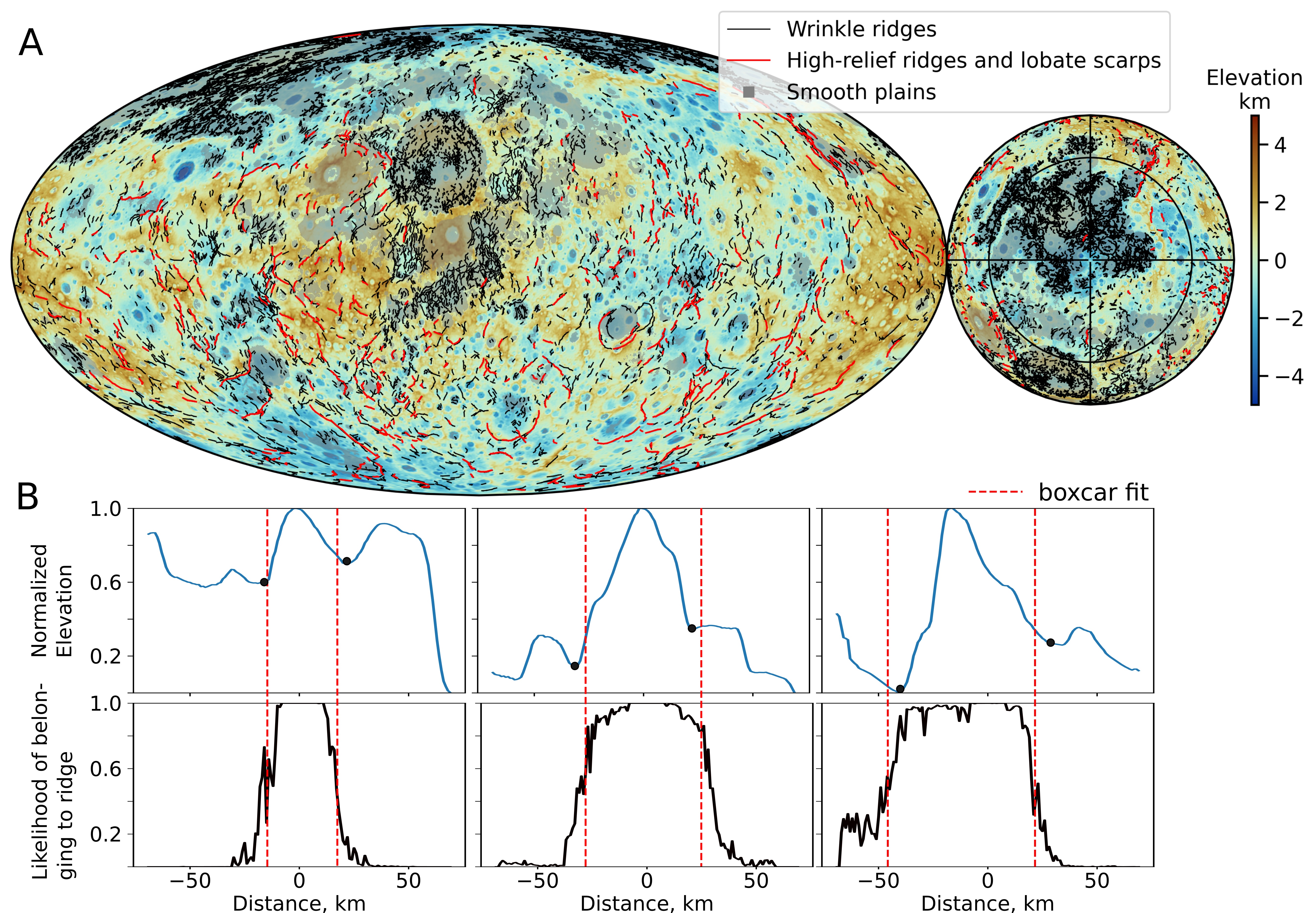

Coupling geophysical inversions and machine learning to unveil Mercury’s geodynamic history

Mercury’s tectonic record is dominated by compressive landforms including lobate scarps, high-relief ridges and wrinkle ridges. Previous analyses of these structures have constrained the planet’s thermal contraction to a range of either no more than 2 km or up to 7 km. This important discrepancy have strong implications for our understanding of Mercury’s geodynamic history and results from different interpretation of the tectonic record. In Broquet & Andrews-Hanna (2024c) we improve upon previous work by considering the contribution of flexural strain to the tectonic record, proposing a consistent mapping of primary tectonic landforms, and making use of machine learning to analyze all compressive landforms rather than relying on displacement-length ratios (Figure 2). We show that when considering the entire tectonic record of Mercury, global contraction averages to 6.3 km. Removing small secondary ridges that are parallel and in close vicinity to a primary longer ridge reduces contraction to about 3.5 km, which is substantially higher than when neglecting wrinkle ridges (~1.2 km). Tectonic strain exhibits prominent lateral variation in all scenarios, with some regions experiencing near-zero contraction, while others recorded several kilometers of deformation. This is interpreted to be due to local plume-induced flood volcanism sequences, variable crustal heat production, or a change in the planet’s orbit and associated surface temperature. Our tectonic strain history indicates a period of rapid contraction from 4.1 to 3.9 Ga, followed by more steady cooling, which have implications the planet’s geodynamic history. Based on an inversion of present-day gravity and topography for crustal deformations, we show that flexural strain can counteract contractional strain as well as add to it. Although some regions with tectonic strain excess and deficit can be explained by local lithospheric flexure, the net effect of flexural strain on global contraction is negligible.