Mars

Preamble

The strong and cold, outermost portion of a planet is conventionally referred to as the lithosphere. When this layer is loaded by volcanoes or polar ice caps, it deviates from its original state and bends. This compensation mechanism gives rise to two principal observables that are detectable from orbit: gravity anomalies and topographic landforms. These data can be used along with a geophysical model to invert for key parameters such as the density and composition of the loading material, and the strength of the underlaying lithosphere. Lithospheric strength/rigidity is typically modeled assuming that the lithosphere is entirely elastic and using a mathematical construct – the elastic thickness of the lithosphere. The strength of the lithosphere and the amount of bending that can be sustained is inversely proportional to the elastic thickness. The elastic thickness can also be linked to the thermal state of the interior and provides important constraints for the geologic evolution of planetary bodies (for more information, see my TeHF package).

The gravitational signature of Martian volcanoes

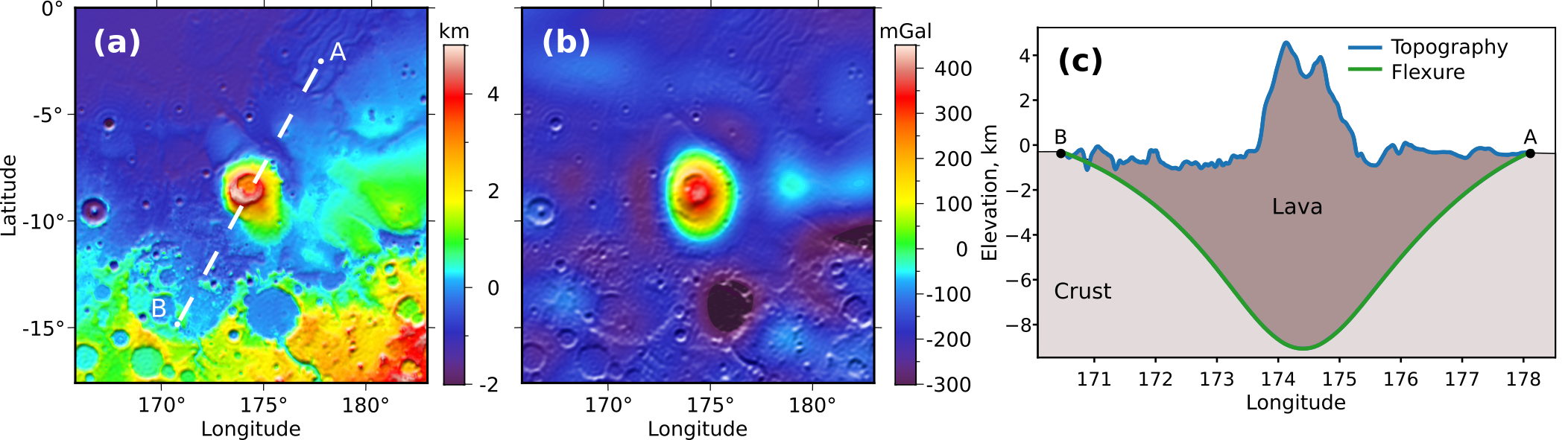

In Broquet and Wieczorek (2019), we analyze the gravitational signature of 18 kilometer-sized Martian volcanoes. We model the deformation of the lithosphere under the volcanic loads and compare the resulting theoretical gravitation signal to observations (Figure 1). The mean bulk density of the volcanic structures is found to be 3200 ± 200 kg m−3, which is representative of iron-rich basalts, as sampled by the Martian basaltic meteorites. The elastic thickness of the lithosphere is constrained to have been thin, <15 km, when the old volcanoes (>3.2 Ga) formed. This implies that the lithosphere was hot and thin early in geologic history. Conversely, most of the younger and prominent constructs within the Tharsis and Elysium provinces (3 Ga) were emplaced on a colder and thicker lithosphere, 30 to 100 km, which is consistent with the bulk of their emplacement occurring later in geologic history.

The present-day thermal state of Mars: Lithospheric deformation beneath the north and south polar caps

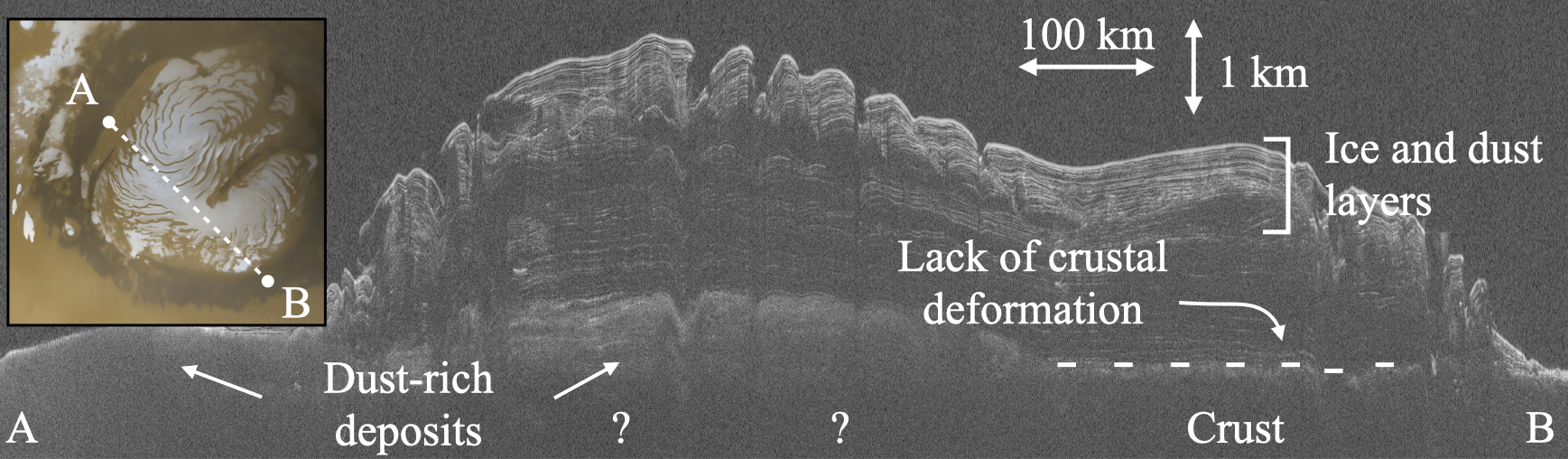

Mars harbors two geologically young (<100 Ma) and large (~1000 km across) polar ice caps that represent the only million-year-old surface features that induce measurable surface deformations. In the absence of in situ heat flow measurements, the analysis of these deformations is one of the few methods that give access to the present-day thermal state of the planet The latter is indicative of the concentration of radiogenic elements in the interior, which is an important metric to determine the planet’s bulk composition, structure, and geologic evolution. In Broquet et al. (2020) and Broquet et al. (2021) we make use of radar data to image the deformed basements beneath the two polar caps (Figure 2). Together with a geophysical model, we show that the elastic thickness beneath the north pole is >330 km, whereas it is >150 km beneath the north pole. The work provides a critical tight anchor point on the present-day interior thermal state of Mars, which has been widely used in the Martian geophysics community (e.g., Khan et al., 2021; Pou et al., 2022; Plesa et al., 2022). The study further provides the first geophysical estimate on the composition of the north polar cap finding a non-negligible quantity of CO2 ice, which has implications for both the orbital history of the planet and the occurrence of melting at the base of the polar cap.

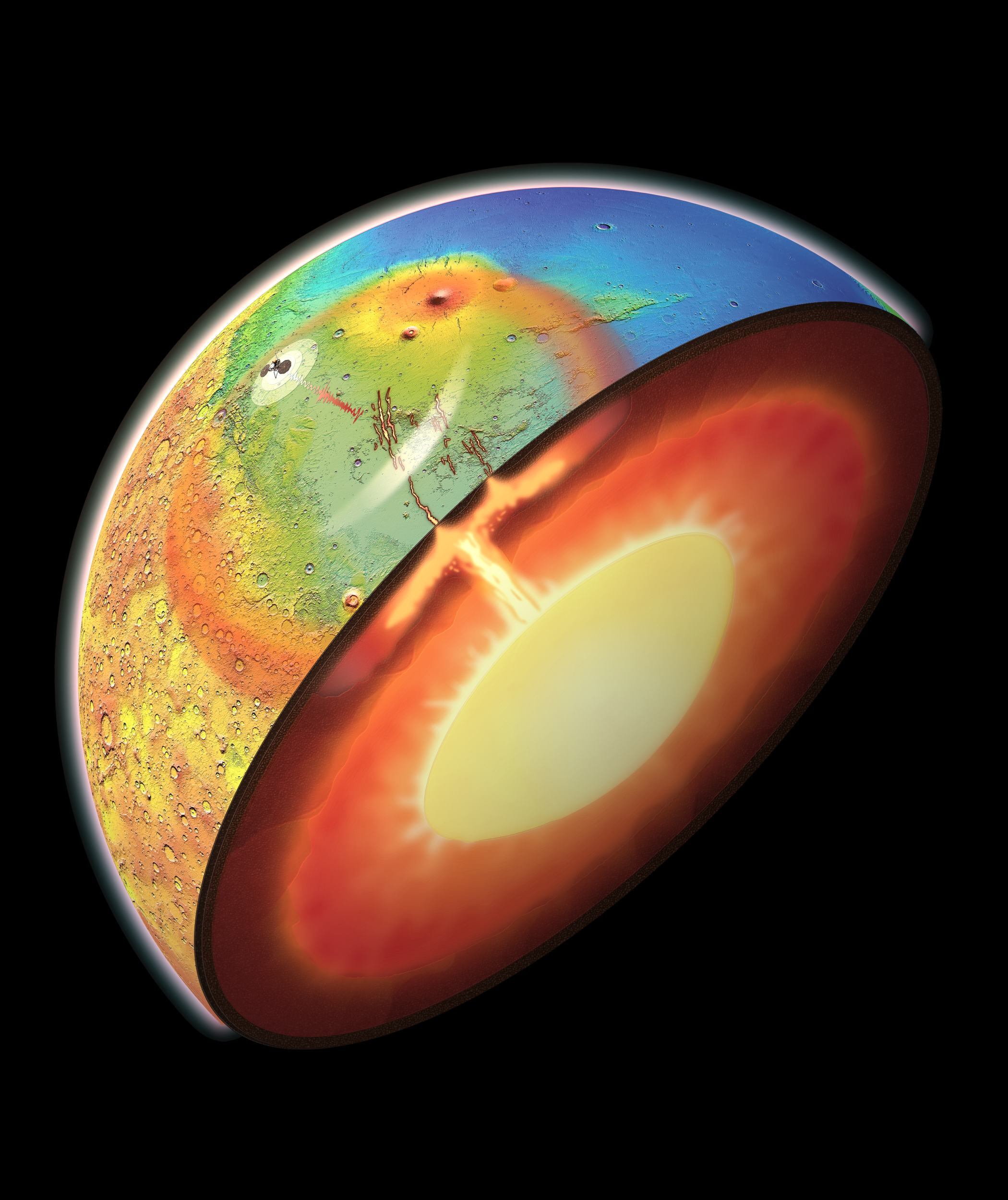

A giant active mantle plume underneath Elysium Planitia

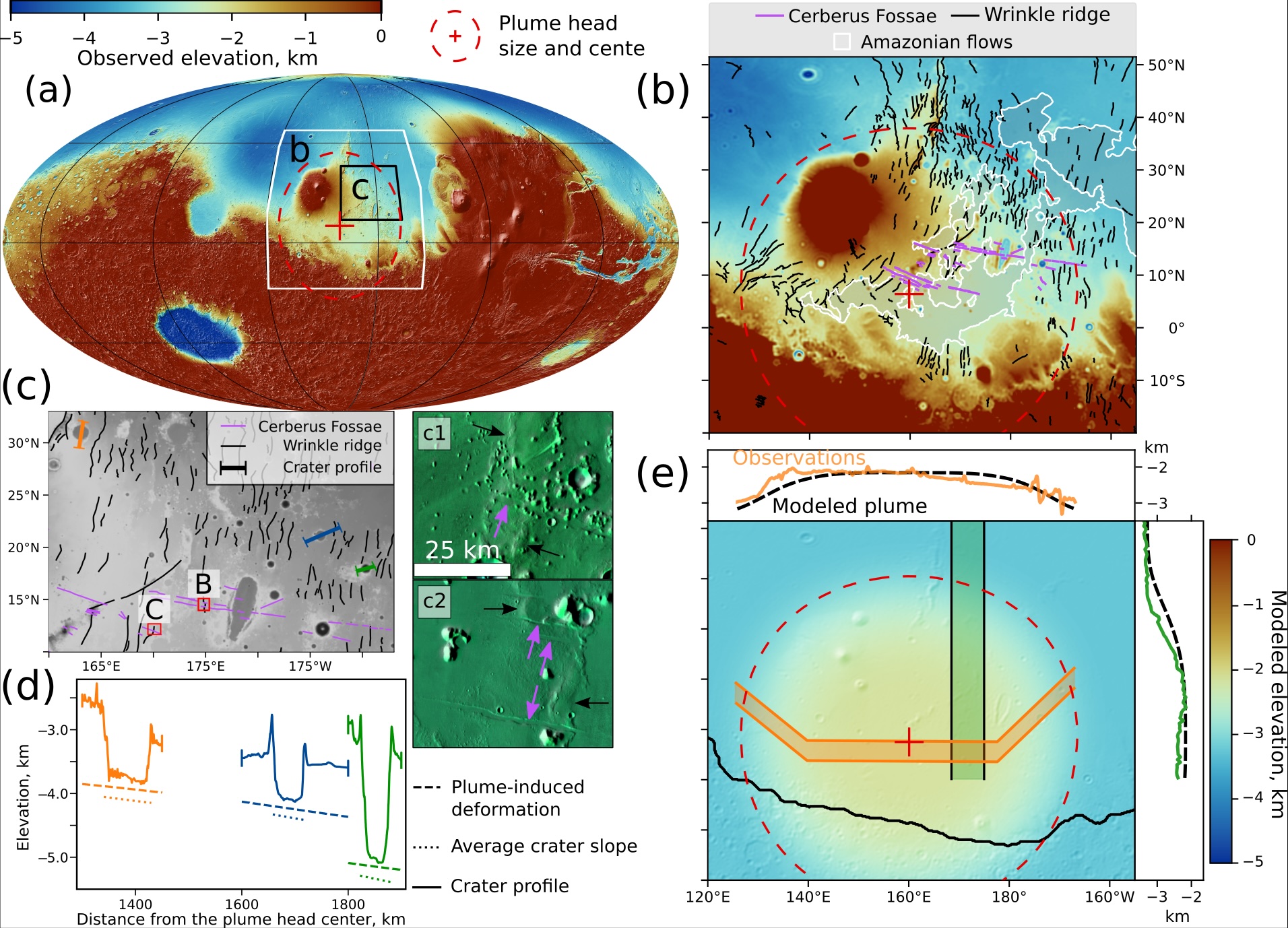

In Broquet & Andrews-Hanna (2023a) we addresses an important open question regarding the origin of the young volcanism, and on-going seismicity recorded by InSight, in the nondescript Elysium Planitia region. Through a comprehensive analysis of orbital data and geophysical models, the work reveals that the planitia is currently underlain by a 4000-km mantle plume head driving the regional volcano-tectonic activity (Figure 3 & 4). This demonstrates that Mars is geodynamically active today. The discovery is a paradigm shift for our understanding of the thermal evolution of Mars and other stagnant lid planets, as major plume events are generally not predicted to occur on cooling bodies. The work further shows that InSight landed on top of an active plume head, a thermal anomaly that has to be considered by future studies. This work provides the first direct evidence for an active plume on Mars, with profound implications for the planet’s thermal evolution and interior structure.

Mantle plumes and Mars’ tectonic history

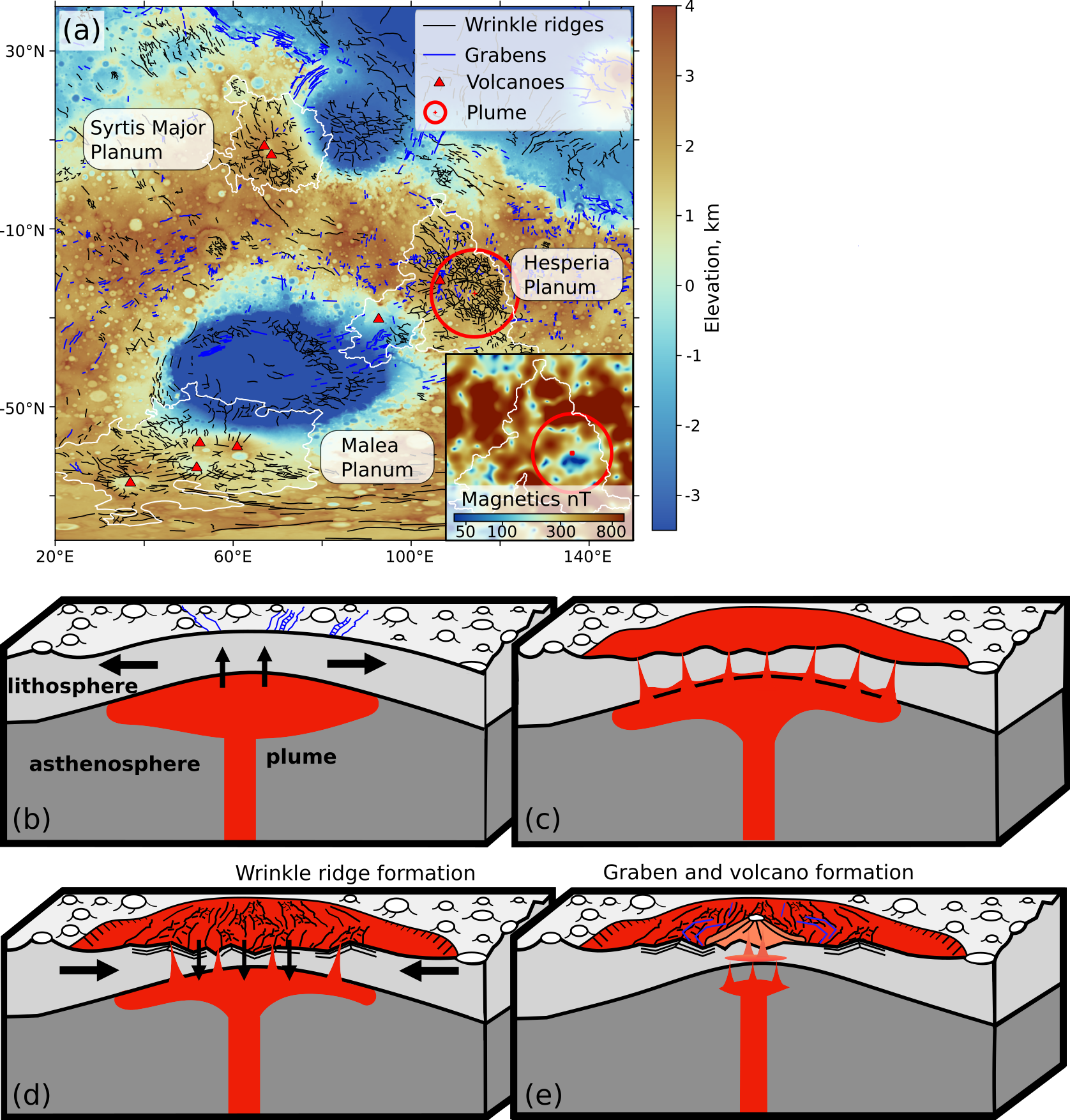

In Broquet & Andrews-Hanna (2023b), we investigate Hesperia Planum (Figure 5), a volcanic plain that formed during a geodynamically active, yet poorly understood, epoch in Martian history called the Hesperian (3.7–3.4 Ga). Through detailed mapping and analyses of tectonics, magnetic and gravity anomalies, the work reveals that Hesperia Planum had a similar evolutionary path to terrestrial plume-induced flood basalt provinces. This provides the first observational evidence for the occurrence of mantle plumes on early Mars, away from the vast Tharsis volcanic province. Our inversion constrains the plume thermal anomaly, width, and exact location. Together with additional work in Andrews-Hanna & Broquet (2023), we suggest that the thermal evolution of Mars may have been less steady than previously thought, with major plume events distributed throughout the planet’s surface, which has implications for the history of melting in the Martian interior.